Wrapping up the 2021 harvest at his Willamette Valley property, Jim Bernau felt excitement and a great sense of relief. “I think the flavors in the Pinot Noir are the best I’ve tasted since 1988,” says the Willamette Valley Vineyards founder. “The yields were below average…and that tends to provide more opportunities for flavor.”

Ed King, CEO of King Estate Winery, is similarly enthralled. “Our harvest is complete and I’m thrilled we’ve had no smoke issues in the Willamette Valley and that we’re seeing fruit of very high quality,” he says. “A lot of things have gone right in the vineyard this year and that’s going to pay off in the cellar.”

The early enthusiasm for the 2021 harvest in Oregon comes at a time when the state is seeing increased demand for its Pinot Noirs and other wines, despite recent upheavals. In 2020, vintners had to deal with the dual challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic, which shifted consumption patterns, and September wildfires that produced smoke exposure challenges in certain vineyards and regions.

“There were two different stories,” says Colin Eddy, vice president of sales for Hyland Estates and NW Wine Co. “There was the pandemic itself and then there were the fires later in the year. We not only had the issue of a national pandemic but fires that impacted the production levels of wines for us. We had wine to sell and we shifted our efforts almost exclusively into retail and we did very well. [And we took action] to combat the smoke taint, and we feel like what we did worked.”

Generally speaking, Oregon wines fared well in 2020 despite the pandemic that shifted nearly all consumption away from the on-premise and into retail. Sales volume in the U.S. held steady at 4.6 million 9-liter cases, according to Impact Databank, but value continued to inch up, and is rising again this year. Oregon table wines boasted an average retail price a bottle of $16 a 750-ml. in IRI channels in the year-to-date through October 31—more than twice the national average of $8, according to Impact Databank. Oregon table wine’s off-premise volume growth was a modest 0.1% year-to-date according to Nielsen, but still outperformed California and Washington wines—down 10.9% and 12.5%, respectively, on a tough comparison after last year’s off-premise surge—as well as imports, which were down 9.2%.

According to the Oregon Wine Board, the Oregon wine industry generated revenue of $699.6 million last year, an increase of 4%. That compares to less than 2% dollar growth for the total wine market in 2020, according to Impact Databank.

Major brands were in the driver’s seat last year, benefitting from the consumer switch to retail in a way that smaller producers, typically without major retail chain listings, were unable to do. “The story of Oregon in general is a little bit of a tale of two cities, because if you had retail placements in 2020, that was very good,” says president and CEO of A to Z Wineworks Amy Prosenjak. “A lot of the smaller wineries that rely on direct sales and tasting room traffic definitely had a harder go of things.”

Prosenjak says her company’s Rex Hill label struggled because of its reliance on direct sales, while the much larger A to Z label benefitted from a strong focus on retail in recent years. A to Z is the second-largest Oregon wine brand in the United States and posted a 15% increase to 359,000 cases in 2020.

A to Z was one of four brands among the top eight to post a double-digit gain. The others were Willamette, which jumped 15.3%; King Estate, which increased 11.6%; and The Four Graces, which grew 15%. Oregon’s leading brand, Underwood, registered a 5.5% increase to 410,000 cases. Growth for Underwood, available in both 12-ounce cans and 750-ml. bottles, has been spurred by its Rosé Bubbles canned variant ($6), which has “been on a rocket ship ride” that is expected to result in depletions north of 100,000 cases this year, according to Adam Coremin, vice president of sales for Underwood brand owner Union Wine Co. Underwood Gold Bubbles is on a similar trajectory with about half the volume, he adds.

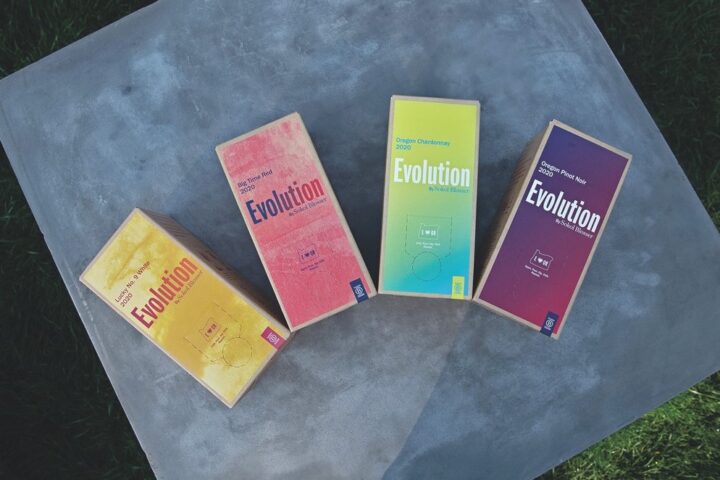

The use of alternative packaging such as cans, which have been a huge boon for the Underwood brand, or bag-in-box is relatively rare for Oregon wineries, but it’s gaining steam in the current environment. Sokol Blosser Winery launched a bag-in-box option in 2020 as a pivot to help weather the pandemic. “Our on-premise business declined exponentially and our tasting room closed, but we thought inside the box and decided to launch Oregon’s first boxed wines for national distribution, under our Evolution brand,” says CEO Alison Sokol Blosser. “Our first run of Evolution Lucky No. 9 and Evolution Pinot Noir launched in July 2020. We followed it up with two new SKUs in 1.5-liter boxes that just launched this year.”

The retail push with unique packaging paid off. “The increases from the box wines and general growth in off-premise nearly made up for losses in the on-premise,” Sokol Blosser says.

Thriving Demand

Whether using alternative packaging or not, Oregon wineries as a group are faring well in a challenging environment. Coremin says Underwood is outpacing the category this year, despite continuing growth for Oregon wines overall in an environment of flat sales for total table wine in the U.S. Others are equally bullish on the performance of the overall sector this year.

Jen Bell, vice president of strategy, analytics, and insights for Ste. Michelle Wine Estates, which owns Dundee Hills-based Erath, says retail is staying strong while on-premise sales begin to bubble again—she points to data showing Oregon wine retail sales up in both value and volume. “This is key because when you look at what happened last year, at this point in time with Covid-19, we had consumers stocking up,” she notes. “So now we’re lapping that stock up in that pantry load, and Oregon wine is still continuing to outperform even the pantry load for last year with positive trends, whereas [other wine regions are] declining.”

And Bell predicts the on-premise will return full-force. “Consumers will shift their dollars more to on-premise as the big celebrations and dinners out happen again,” she says.

Bernau agrees that Oregon wines are thriving, noting that at this point it’s mainly in retail. “Oregon is on fire with consumers,” he says. “If you look at Nielsen scan data, Oregon leads the nation among identifiable wine regions. Also, we lead the nation in what we’re receiving for our wine from the consumer.”

Retailers around the country also report strong demand. Jay Kam, president of Honolulu’s Vintage Wine Cellar, says despite the relatively high prices commanded by Oregon wines, the state’s wineries “are producing some of the best price-to-quality ratio Pinot Noirs in the market.” He says the 2018 Domaine Drouhin ($44 a 750-ml.) and 2018 Roserock ($36) Pinot Noirs lead the field at his store.

Dustin Mitzel, CEO of North Dakota’s Happy Harry’s Bottle Shops, says demand has accelerated over the past five years even as prices edge up. The sweet spot for Oregon wine pricing in his stores is $15-$20, “maybe stretching into $25.” Leading labels include Sokol Blosser Evolution White ($15 a 750-ml.), A to Z Pinot Noir ($19), Erath Pinot Noir ($20), Elouan Pinot Noir ($20), and Willamette Valley Vineyards Riesling ($14). “In the higher-end price points Willamette Valley Vineyards Pinot Noir ($29) has done very well,” he adds.

Direct-to-consumer sales are also on the rise. Sovos ShipCompliant reports that among all major wine regions in the U.S., only Oregon increased volume shipped direct to consumer in the first six months of 2021. Oregon averaged 21.3% growth during that period. ShipCompliant adds that Oregon crossed the $40 mark for the first time, hitting an average bottle price of $41.

Managing Expectations

The enviable trends and strong enthusiasm for the Oregon wine sector could be tempered by a potentially precarious situation: supply shortfalls and rising prices. In 2020, yield per acre decreased by 24%, attributable to cooler late spring weather reducing cluster sizes and weights, according to the Oregon Wine Board. Total grape production was down 29%as yields and September wildfires resulted in 30,000 fewer tons harvested than the prior year.

While 2021 is expected to be an improvement in volume over 2020, vintners this year reported lighter-than-average yields. On top of the 2020 shortfall, that could pose problems.

Hyland Estates’ Eddy says the impact of the 2020 wildfires, which hit both Oregon and California, is being felt now in white wines, with red wines up next. “There’s a huge vacuum right now with the issues the entire west coast dealt with in 2020, especially with white wine,” he says. “I think the red wine vacuum is next. This is the time when people would just start releasing those 2020 reds— now and [over the next year or so]. It wasn’t just Oregon that was impacted by these fires. It was California too. Retailers are continuing to sell more wine than they did previously but the entire west coast Pinot Noir production is down 30% or more, so there’s some opportunity to fill that vacuum.”

Some wine companies say they’ve been managing current inventories to help stave off a potential shortfall in the coming year or two. Bell of Ste. Michelle Wine Estates says the company has reconfigured allocations of the 2019 vintage of the popular Erath wines to, in essence, stretch the supply as far as possible, thus easing the demand for the 2020 vintage.

The formula will likely be complicated by what many feel are inevitable price increases. “Trend-wise, we’re seeing people take price increases, and I think we’re going to continue to see that with the rise in cost across the board,” Eddy says. “Anything that comes from another country is delayed and more expensive these days.”

Sokol Blosser sees an array of challenges related to pricing. “I haven’t had a single conversation with a distributor or buyer where the topics of price increases, freight challenges, or supply shortages hasn’t come up,” she says. “Unfortunately, it’s inevitable that there will be price increases. The cost of goods increases that we have experienced in the past six months have been significant. Glass prices are up 38%-52%, if we can even get the glass. The cost to hand-pick our vineyards this harvest went up 28%. The cost to ship our product to California for distributors to pick up went up 60%. Everyone along the chain from grape to glass is experiencing the same thing, so it is inevitable that consumers will start to see price increases on the shelf soon.”

For A to Z Wineworks, which targets the under $20 price band for its wines, the increasing costs will have a big impact. “Our strategy has always been to produce the highest quality wine for the greatest sustainable value,” Prosenjak says, noting that with supply chain challenges, as well as the increasing costs of goods and labor, it will be difficult to hold the line on prices. “It’s going to be hard for all companies to maintain their margins so we’ll have to continue to take a hard look at that.”

Those challenges will be felt not just by Oregon wineries but by the wine industry as a whole. But Bernau believes that Oregon—especially the Willamette Valley—is well-positioned to weather the changes. Unlike many other wine regions, Oregon has managed to keep the majority of its volume in the $12-and-above price segment rather than fighting for share in the sub-premium pricing tiers. “We’re far less price sensitive, especially Willamette Valley-appellated growers and producers, because the consumer is already willing to pay for high quality Willamette Valley-appellated wine,” he says. “As an industry we’re probably not as vulnerable to cost pressures and having to recover those cost pressures through pricing. It’s still a concern. We want to make sure we deliver a great product at a fair price to the consumer, and we’ll have no choice but to recover some of these increased costs the industry is facing.”

Sustainability In Focus

Oregon thus far has managed to maintain its premium focus in part because of the predominance of smaller wine operations and vineyards cultivated using sustainable practices. “There’s a wonderful ethic in Oregon about the wine business and the wine industry,” says King. “It’s still an artisan business. The love of Oregon and wine continues to be the tale, and the commitment to quality and really taking advantage of the cool climate opportunity we have here has continued to mean that the customers are finding us and enjoying the wines, and the aficionados certainly enjoy the wine.”

Like the majority of Oregon wineries, King Estate “believes in sustainable farming and certainly looks askance at some of the alternatives,” King says.

“It’s an industry-wide commitment,” agrees Bernau. “We have many colleagues who share the same values. We wouldn’t do it any other way, regardless of what the consumers thought of it. We’re continuing to make advances in reducing our impact on the environment.”

But how that commitment manifests depends in large part on the individual winery. While sustainable practices are a way of life in the Oregon wine world, individual wineries are in various stages of working toward that goal. For some, reaching thresholds for organic or biodynamic or other sustainable practices is still a work in progress. For others, like King, the larger issue of carbon footprint—everything from the glass packaging to the shipping impact on the environment—is front and center.

No matter the stage of development, King says the authenticity of the Oregon wine culture is sincere. “It hasn’t turned into big business yet,” he says. “We’re still that band of winemakers that came here some decades ago and started it all. We work together as best we can. There are differences and disagreements between regions and the state about regulations and this and that, but at the end of the process we’re at the table and we’re thankful that we’re not some other wine regions.”