As the craft beer industry has mushroomed over the past decade, brewers raced to produce the maltiest, hoppiest, most alcohol-fueled extreme beers—with intimidating names to match. For example, Indiana’s 3 Floyds Brewing Co. has its Dreadnaught IPA, Zombie Dust pale ale and Tiberian Inquisitor Belgian-style ale. But the American consumer may now be lurching in the opposite direction. Brewers who once were preoccupied with boosting the strength of increasingly exotic brews are now reducing alcohol content in their IPAs and Pilsners, without losing too much flavor or mouth feel.

Session beers are coming into prominence, as both a relief valve for consumers tired of big beers and as a gateway to craft beer for mainstream consumers. With most national-brand lagers topping out around 4.2-percent alcohol-by-volume (abv), craft offerings with 7-percent abv or higher have seemed like too much of a tasting leap.

Defining A Trend

The rise of session beer has been accompanied by a debate over its definition. “Session” is a British term originally meant to identify beers light enough in alcohol to be drunk continuously over three or four hours. In England, session beers are commonly under 4-percent abv. A few years ago, Beeradvocate.com promoted a cut-off of 5-percent abv for American beers to be defined as sessionable. More recently, whisk(e)y writer Lew Bryson, who started a blog called “The Session Beer Project,” has settled on a middle ground of 4.5-percent abv. American brewers continue to use the session moniker for beers that fall between 4-percent and 5-percent abv, and sometimes even higher, so the issue is far from settled.

There are also no set guidelines on the proper way to make a session beer. Reducing the alcohol content is liable to result in a thin, watery beer that lacks body. Some brewers are incorporating hops later in the process to help achieve intense hop flavor and aroma. Others are experimenting more with unusual malts and yeasts and even using hop extracts to pump up the texture and taste profile of their beer.

Bill Sysak, an ambassador for Stone Brewing Co. in Escondido, California, says a rising number of on-premise customers are requesting “light” beers. “Much of the time, they aren’t talking about calories—they’re talking about alcohol,” he says. “People are health-conscious nowadays and don’t always want an über-beer.”

For the past year, Stone has offered its Go To IPA, which clocks in at 4.5-percent abv and a surprisingly robust 65 IBUs (International Bittering Units). Brewmaster Mitch Steele employs a method called “hop bursting,” which he says adds an “irrational” amount of hops near the end of the boil in the brew process, coaxing out aromas of peach, citrus and melon to result in a classic tasting IPA. The company’s second session beer is Levitation amber ale at 4.4-percent abv. “Both these brews sell really well,” Sysak says. “Retailers are making space for session beers.”

Low-Alcohol Focus

Chris Lohring, founder and owner of Notch Brewing Co. in Ipswich, Massachusetts, says he saw this trend coming. He launched his business in 2010 with the goal of producing only session beers. The company’s best-seller is a 4-percent abv Czech-style lager called Notch Session Pils, followed by its Left of the Dial IPA at 4.3-percent abv, and the acidic and tart Hootenanny Berliner weisse at 3.3-percent abv. Lohring harkens back to many Old World brewing styles in his production.

“When I started four or five years ago, people complained I was using gimmicks to dumb down beers,” Lohring says. “But people have been making beer like this for hundreds of years.” Most session brews—Notch offerings included—are priced at the same levels of other craft beers, from $7 to $10 a six-pack and around $15 a 12-pack. Arguing that low-alcohol offerings should be priced lower because they use fewer ingredients, some skeptics are suspicious that session brewers may be taking extra margin. But Lohring explains that brewers must typically seek out more expensive and exotic hops, malts and yeasts to keep the flavor in their session beers. Besides, he notes, the ingredients account for less than 20 percent of the price of a can of beer.

Lohring also contends that session beers can build better business for any bar or restaurant. “Some of the best beer bars in Boston were noticing that their customers would have one brew and leave an hour later, but that the session customers would order second and third beers and hang around longer,” he notes.

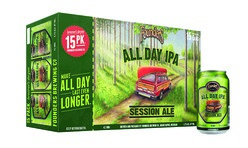

Jeff Van Der Tuuk, beverage director at SideDoor gastropub in Chicago, stocks several session offerings. At a recent beer dinner, he paired the 3.8-percent abv Goose Island Lilith Berliner weisse ($9 an 11-ounce pour), with a salad featuring macerated blackberries and a citrus vinaigrette. Van Der Tuuk is also a big fan of the 4.7-percent abv Founders All Day IPA, which is typically on his summer beer list. “A lot of beer drinkers are against session IPAs,” he says. “They somehow think the low alcohol affects the quality and reduces it to something less than a real IPA. I explain it’s a variation, just as an imperial IPA at 9-percent abv is a variation. If brewmasters are allowed to go in that direction, then why can’t they go toward lower alcohol, too?”

SideDoor also serves the 4.7-percent abv, California-brewed North Coast Scrimshaw Pilsner ($8 on draft), which Van Der Tuuk admires for both its quality and consistency. “For Bud Light or Miller Lite drinkers coming through the door, I can offer that beer, and they’ll be very content,” Van Der Tuuk explains. “In fact, it’s our best-selling brew. If I’m trying to navigate a beer drinker in a fresh direction, I’ll usually start with Scrimshaw and then later move on to a pale ale or Berliner weisse.”

Year-Round Appeal

At Founders Brewing Co. in Grand Rapids, Michigan, COO Chase Kushak says the All Day IPA is the company’s best-seller, easily outdistancing more potent stablemates like the 8.5-percent Dirty Bastard Scotch Style ale. He’s noticed more competition in the session segment and a movement away from the image of low-alcohol beers being consumed strictly during the summer. “We see significant spikes in our All Day IPA sales around the winter holidays,” Kushak adds. Last year, the company introduced 15-packs of 12-ounce cans ($17 to $20). “The beer sells well in places like ski resorts because of the convenience of the can, and it allows people to drink and ski without worrying about falling down.”

Still, warm climates apparently spur interest in session beers. Sunny San Diego County is home to some 100 craft brewers, and many are rushing to market with session beers. Ballast Point Brewing Co.’s Even Keel Session IPA comes in at a slim 3.8-percent abv. “We sell it in 27 states, and in some markets, it’s more of a spring and summer beer, but in Southern California, it’s year-round,” says Hilari Cocalis, director of marketing at Ballast Point. “In this region, people spend a lot of time outside and near the water, so a low-alcohol beer makes good sense here.”

Robert Rentsch, senior director of brand marketing and portfolio development for the Portland, Oregon–based Craft Brew Alliance (CBA), says low-alcohol beer makes just as much sense in the Pacific Northwest. CBA’s portfolio of brands includes the 4.2-percent abv Widmer Brothers Blacklight IPA, launched last year, and the new Widmer Brothers Replay IPA at 4.5-percent abv. The parent company’s Kona brand offers the 4.4-percent abv Big Wave golden ale, and the Red Hook brand markets the 4-percent abv False Start IPA. CBA has also developed a 4.6-percent abv session pale ale called Game Changer for the Buffalo Wild Wings restaurant chain. “We’ve noticed a real uptick in bars listing alcohol content and IBUs,” Rentsch says. “As a result, consumers are buying more session beers.”

The display of the actual alcohol content may be the best solution, since the session definition is still fuzzy in many places. For instance, Full Sail Brewing Co. in Hood River, Oregon, has a whole line of beers labeled as session that range from 5.1-percent to 5.4-percent abv. Irene Firmat, the founder and chief executive of Full Sail, is unapologetic. “Session for us is a brand,” Firmat says. “We believe the most interesting beers are all between 5-percent and 6.5-percent abv. Go under 5 percent, and beer becomes less interesting.”

Session brews continue to get better. Brian Jensen, the owner of the two-unit San Diego retail outlet Bottlecraft, recalls his introduction to sessions a few years ago. “Brewers were cutting back on the malt, and the body of the low-alcohol beers ended up too thin,” he says. “I wanted more.” Jensen, whose stores stock about 700 beer SKUs, has since observed some improvement in that arena. “Brewers seem to be adding rice, oatmeal or other ingredients to achieve a better viscosity,” he explains.

Most significant to Jensen, “session beer” is now a term his customers use when requesting brews. “Two years ago, nobody around here knew what session beers were,” he says. “Now it’s a name that people recognize. We’re hearing that customers want a beer that’s lighter, but doesn’t lack in flavor. Session fits the bill for them.”