In 2005, when Ralph Erenzo founded Tuthilltown Spirits in Gardiner, New York, his friends and relatives responded with confusion and skepticism. Small-batch spirits? New York Bourbon? They’d never heard of such a thing. Why would he want to go into the beverage alcohol business—the most highly regulated, highly taxed industry in the world? “Everyone thought I was nuts,” Erenzo says.

Ten years later, they’re no doubt singing a different tune: Tuthilltown has emerged as one of the great successes in the first wave of new American distillers—those who launched their businesses between roughly 2005 to 2010. More than 500 craft spirits producers are now operating in the United States, and the trade group American Craft Spirits Association (ACSA) expects that number to double by the end of 2016. The industry is growing on a trajectory similar to—and even more rapidly than—craft beer, a category whose sales are projected to exceed $50 billion by 2020. Craft distilling is on fire, and it’s driving the premium to ultra-premium spirits category. “We’re in the middle of a big growth spurt, now that the concept’s been proven,” Erenzo says.

Still, there are significant hurdles to jump. Distillery start-ups are capital-intensive and take longer to turn a profit than many businesses. Competition is fierce from established, larger companies and a ballooning pool of fellow craft distillers—all vying for limited shelf space and the loyalty of retailers. In addition, regressive taxes and permit processes have been a prickly thorn in the side of craft spirits pioneers, many of whom have fought successfully for business-friendly changes to Prohibition-era laws.

Erenzo spent three years lobbying for a bill that would allow New York distilleries to operate tasting rooms. Elsewhere, such efforts have paid off, clearing the way for craft distillers to sell and sample their products on-premise. Sonat Birnecker—who founded Koval Distillery with her husband, Robert, in 2008—has pushed for similar legislation, and today Chicago distilleries are permitted to sample and sell products on-site.

The benefits are increasingly clear to lawmakers, who—having witnessed the rise of craft brewing—see another potential influx of tourism dollars and job growth. “Craft distillers are local people who vote and have influence in their community,” says ACSA founder and executive director Pennfield Jensen. “They’re also bringing dollars into circulation.” Across the board, beverage consumers have embraced locally made spirits, and data shows that small-batch offerings do especially well with millennials.

Corsair Distillery in Nashville, Tennessee, has seen all those factors contribute to a strong performance in the craft space. But when the founders initially started out in 2008, a host of potential investors turned them down, perplexed by their business plan. “We had people tell us that we’d never get on the shelf,” says cofounder Darek Bell—who, along with cofounder Andrew Webber, went on to self-fund and ended up breaking even more quickly than projected. Today Bell and Webber have purchased two new buildings, boosting Corsair’s operating space by 30,000 square feet, and they recently opened a malting facility, which will allow the company to experiment further with alternative grain whiskies. Bell also plans to start growing grapes for brandy in the near future.

“We started in the midst of a tanking economy,” Bell recalls. “It was a terrifying couple of years. We wanted to make unusual spirits, and we weren’t sure how people would react. We’ve won a lot of awards and gotten great feedback—it’s been very vindicating.”

Markets outside of the United States are also strong for American craft spirits. “Everyone is becoming interested in craft,” says Koval’s Birnecker. “We’ve helped set up companies that are only creating for the Asian market. It’s a good time to be in the business.”

Riding the wave of regulatory easing and the success of their forerunners, a second generation of producers now attracts investors that previously looked askance at start-ups like Corsair. “Two or three years ago, it became patently obvious that craft distilling was going to be successful,” says Jensen of the ACSA. “You could hear the checkbooks popping open all across the United States. Now we have an immense number of high-powered, well-funded distilleries coming on line. The next five years are going to be very interesting.

Off-Premise Surge

Although shelf space is a constant challenge, craft distillers receive a warm reception from larger retailers who see benefits in carrying products with strong local followings. “We’ll typically stock a rotation of craft spirits, and when the market permits, we keep longer rotations in our stores that are in close proximity to the producing distillery,” says Romar Nichols, corporate buyer of wine, spirits and beer for Costco.

At Chicago-area retail chain Binny’s Beverage Depot, specialty spirits buyer Brett Pontoni says craft labels represented about 10 percent of his buying in 2014—a proportion he notes is “fairly high.” Binny’s embraced the craft movement early on and last year held its first Craft Distillers Expo, open to all Illinois spirits producers. “We consider ourselves an independent, family-owned company, and we want to be able to support other local companies,” Pontoni explains.

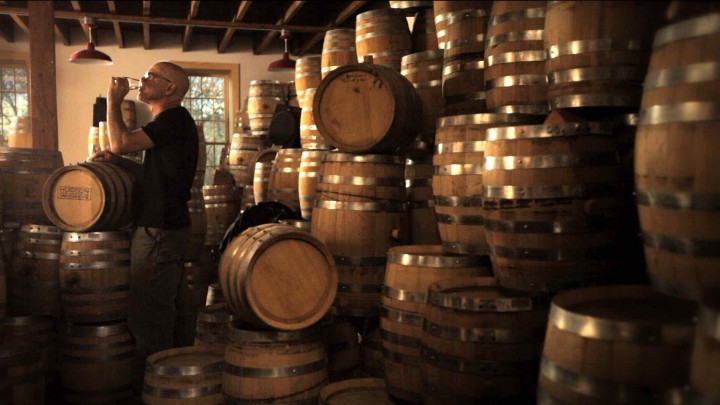

Both retailers and on-premise operators see the strongest craft spirits growth in aged whiskies, now and for the foreseeable future. Typically, craft distillers in the United States have entered the market with a clear spirit—vodka, gin or an unaged whiskey. Meanwhile, many have been laying down barrels, and those whiskies are starting to hit the market, having been aged for at least two years, the minimum recommended for straight American whiskey. Others launched by sourcing and blending whiskies from outside companies and are now distilling and aging their own spirits. In short, aging takes time—but the next few years will see the payoff for the first wave of distillers. “The aging factor of whiskey simply limits its speed to market,” Costco’s Nichols says. “We’ll likely see more whiskies hit shelves as additional barrels achieve the desired maturation time for bottling.”

Pontoni observes that craft whiskies are “getting better and better.” While he views the market as ripe for innovation, Pontoni predicts the more established producers will maintain an advantage in the near future. “They have the highest-quality, most-marketable aged products because they’ve been doing it the longest,” he says. At the same time, Pontoni notes that as the movement matures and distillers improve their craft, a rise in overall quality will likely fuel growth.

Jensen of the ACSA confirms the retailers’ perspective. “It’s the whiskies that are really taking off,” he says. “There’s been an interest in replicating spirits from the old days and a demand for rye whiskey, which was prevalent before Prohibition.” Of the 323 entries in the ACSA’s last craft spirits competition, 155 were whiskies—with much variation within that category.

Defining A Segment

Not all players in the craft space distill their own products. Some producers, such as High West Distillery in Park City, Utah, openly blend spirits sourced from other distilleries. High West also distills its own whiskey, including its two unaged products: Silver Western Oat and Silver OMG Pure Rye. An aged version of Western Oat called Valley Tan debuted in December 2014, and company founder David Perkins says he’ll release additional whiskies when he feels they’re properly aged—perhaps as soon as next year. His decision to source came down to simple economics. “It was clear when we started that it would be hard to build a business without sourcing unless we started with a significant cash flow,” he explains.

Perkins’ transparency has earned him the respect of his peers, who see nothing inherently wrong with the practice of sourcing as long as a distillery doesn’t misrepresent its product. But misrepresentation has occurred elsewhere, with litigious fallout and a spate of media scrutiny of producers whose claims are less than transparent. Lawsuits against Templeton rye whiskey and Tito’s Handmade vodka, for instance, have “given a black eye to the industry,” Corsair’s Bell says. On a more positive note, he adds that the dust-up “has pushed us more toward focusing on unusual, authentic products. It makes us stand out more.”

In Middleton, Wisconsin, Death’s Door Spirits founder Brian Ellison has a similar outlook. He created the company out of a desire to spur agricultural development on Wisconsin’s Washington Island. Death’s Door gin, the company’s best-selling product, is made from wheat grown by the island’s farmers, and other ingredients are sourced in-state. Ellison sees a commitment to this grain-to-glass process as core to his company’s brand identity. “It’d be easy to tell the story and not live the life,” he says. “But we’re telling a story with integrity, and that’s our competitive advantage for the long term. I like that every year at a certain time I’m putting my hands in juniper bushes and picking berries. It reminds me why I’m doing it. I’m not just out there putting juice in a bottle and trying to convince people to pay $30 for it.

Big Buyers

Industry leaders, keenly aware of the craft boom, have responded both with an unprecedented growth of line extensions—aiming to directly compete with craft brands—and by pursuing acquisitions of successful small companies. Taking a cue from successful boutique brands, they’re being more open about the making of their products. “It’s elevated the conversation,” Ellison says. “They’re pointing out that they’re just as craft as anyone else.”

“This is really the first time I’ve seen the big producers having to pay attention to what regional distillers are doing,” says Scott Tarwater, corporate director of wine and special events for restaurant operator Landry’s Inc. Tarwater has noticed large spirits marketers adding numerous SKUs when they previously had only two or three, and he observes that the two biggest growth areas in the company’s beverage program overall are craft spirits—especially whiskey—and craft beer. “We’ve purposefully targeted craft distillers on a regional level, and we’ve clearly helped them achieve their goals along with ours,” Tarwater says.

In 2010, Tuthilltown Spirits became the first craft distillery to sell one of its most successful brands, when its Hudson whiskey range was acquired by William Grant & Sons. “That deal gave us a huge amount of credibility in the industry, and we expect that other distilleries will be acquired,” Erenzo says. “The gospel of craft distilling that I’ve been preaching to major producers is to look to us not as the enemy, but as the future.”

Birnecker says she’s fielded numerous requests to sell Koval, but isn’t interested. Today, the company has 20 full-time employees and is planning to ramp up production four-fold in 2015. “I’m not in this business to sell,” Birnecker says. “My husband and I are working together, and we’re happy. It’s about doing something we love, and we wouldn’t want to compromise.”

That ethos is one of craft’s advantages when it comes to entering new markets. “There’s a sense of family and community around craft distillers,” says Daniel Grajewski, director of beverage for the hospitality company Michael Mina Group. “We feel that’s what we portray too, and we want to work with people who represent that philosophy.”

New Challenges

In the coming years, leaders in the craft space will have to find ways to increase production without sacrificing their commitment to a way of doing business that doesn’t always square with rapid growth—and they’ll face a growing pool of competitors. “Competition from large and small companies is certainly something that keeps me awake every night,” says High West’s Perkins. “There are more and more products out there and only so much shelf space.”

Being a successful craft distiller can present an interesting paradox. “Our main challenge right now is that we’re too small to be big and too big to be small,” says Ellison of Death’s Door Spirits. The company’s products are marketed in the United States by Stamford, Connecticut–based Serrallés USA, the U.S. distribution arm of Puerto Rico’s Destilería Serrallés. With nine full-time employees and a bottling crew of about 10 part-timers, Ellison is proud of how well his gin has done while staying small. “Hendrick’s sells 20 times what we sell,” he says. “How do you tell the brand story to consumers in a way that has integrity, shows the passion and can accelerate? How do you boost sales in a meaningful way without just dumping a lot of money in?”

With more distilleries allowed to sample and sell on-site, Erenzo of Tuthilltown sees the doors opening even wider for innovation. “That’s the beauty of a small distillery,” he says. “We can experiment with a small batch, and it doesn’t cost us much.”

Koval’s Birnecker agrees. “Craft bottlers have room to be incredibly creative,” she says. “There’s a lot of innovation coming out of the craft industry right now, and I don’t see that slowing down.”

Indeed, it’s a good time to be in the craft business, but Erenzo is glad he got in when he did. “Our timing was perfect, and the market was perfect,” Erenzo says. “The field now is very crowded. There are a lot of producers putting out extremely good spirits right now.”